♛

____________________________◦✴︎◦____________________________

♛

Postscript / Prescript: A few words about the history of this article; about the subjective nature, not so much of history itself, but of the telling of history; and the relevance of the term, ‘Sins Of Omission’.

Several years ago, ironically around the time my father died, I was asked to write ‘about’ 4000 words for a piece on the history of surfing in Virginia Beach for the Richmond-based magazine Virginia Living. Accidentally, I wrote ‘about’ 40,000. Ouch. A few years later, in a roundabout, serendipitous way, (t.a. Bobby Fisher) the article morphed into a formidable re-write for The Surfer’s Journal. Amidst all those thousands of words were obscure mentions, vernacular minutia, fuzzy ruminations, conspicuous name-drops, clique-specific anecdotes, and so forth. But in going from 40,000 words to 4000, things are going to get lost. Lost. Cut. Etcetera. The local in you wants to shout-out to every single significant bro & bro-ette that ever was. Publishers and editors on the other hand will counter that certain things which may have a particular local attraction, have far less context, and therefore appeal, for broader national and even international readerships. Which admittedly is, like-it-or-not, true. At the end of the day though, both things are true: the losses suck; but losses happen. Sometimes you’re the windshield / sometimes you’re the bug. Bottom line is, writing an article like this is . . . hhhhhhhard. For some, a good deal of the material contained here will be brand new. For the rest? Well . . . as Groucho Marx is often cited, “If you've heard this story before, don't stop me; I want to hear it again."

Additionally, what I attempted to focus on from the start, was an oral history; a pre-GoPro™ history. My Aunt Jennie who died in the early 90’s remembered the late 19th century. As a child I had the great privilege of meeting and being shown some of the personal collections of Norfolk historian and photographer Caroll Walker, who himself remembered the earliest years of the 20th c., and whose parents directly knew the times of The Civil War. Mr. Walker did not Twitter. Nor did he blog or Facebook. Aunt Jennie did not Instagram. Nor did Kerouac. Mid-century, post-war Beatniks were all about ‘the oral tradition'. Period. It’s one which goes back to Homer, Socrates, and The Bible. I have no idea whether or not some postmodernist egghead has already muttered this down to a theory, but to my mind, oral history, and by extension, history in general as we've known it, ended the day the internet-linked computer machine mirage'd itself. . . shackled itself into ubiquity. Under present technological conditions, history is being written by almost everyone, almost everywhere, explicitly every minute. The posterity of this present day and age is being served just fine thank you very much. Although the line between historical posterity and crass narcissism IS often Rothkoesqely blurry. An article requires focus, and my primary focus has been the endangered nature of oral history to the exclusion, more or less, of the altogether thriving nature of present tense history.

__________________________________________________________

“Would love to talk to you about the good old days, but the good old days are here right now."

-Kurt Smaltz, 2013

__________________________________________________________

"Nostalgia burns in the hearts of the strongest . . .”

-David Sylvian, 1984

__________________________________________________________

‘The devil of it is is that there is but one truth, but many smaller relative truths; each exhibiting the seemingness of being equally true.’

-graffiti, Goa, 1968

__________________________________________________________

__________________________________________________________

∙ ∙ ∙ ◦✴︎✺◎♛ VB ♛◎✺✴︎◦ ∙ ∙ ∙

A History Of Surfing In Virginia Beach /

The Surfer's Journal, No. 23.6 / Dec-Jan 2015

For more than a hundred years, surfers in Virginia Beach have been tracking, riding, and designing their lives around every ounce of energy they can wring from the Atlantic.

By Stewart Ferebee

Boards in arm, three teens in their thirties go cycling along the feeder road leading into the low-rise suburban sprawl of the Northend, past the balmy low-slung Live Oak grove and the frilly bejeweled Mimosa, speeding by, on windless endless days of summer. Light northwesterlies now hone clean the aquatic corduroy of an oily slick daybreak Atlantic, countering sideways with sideways, wind for swell. Drawing lines in their heads as they pedal in anticipation; there already in psychic momentum before they've ever even touched the water. This is what we pray for.

In the grand scheme of things, this is not a place known for its quality surf. The culprit is a 300-mile-wide, energy-sapping joy-killer—the Continental Shelf, which mockingly imposes itself off much of the East Coast, reducing Atlantic swells before they reach the shoreline. But surfing in Virginia Beach has a history, a formidable one that goes back 100 years and comprises multiple generations. And there is a story to go with the tradition, populated by a handful of intrepid thrill-seekers in the early decades of the 20th century, and now, by modern throngs seeking their own expression and recognition.

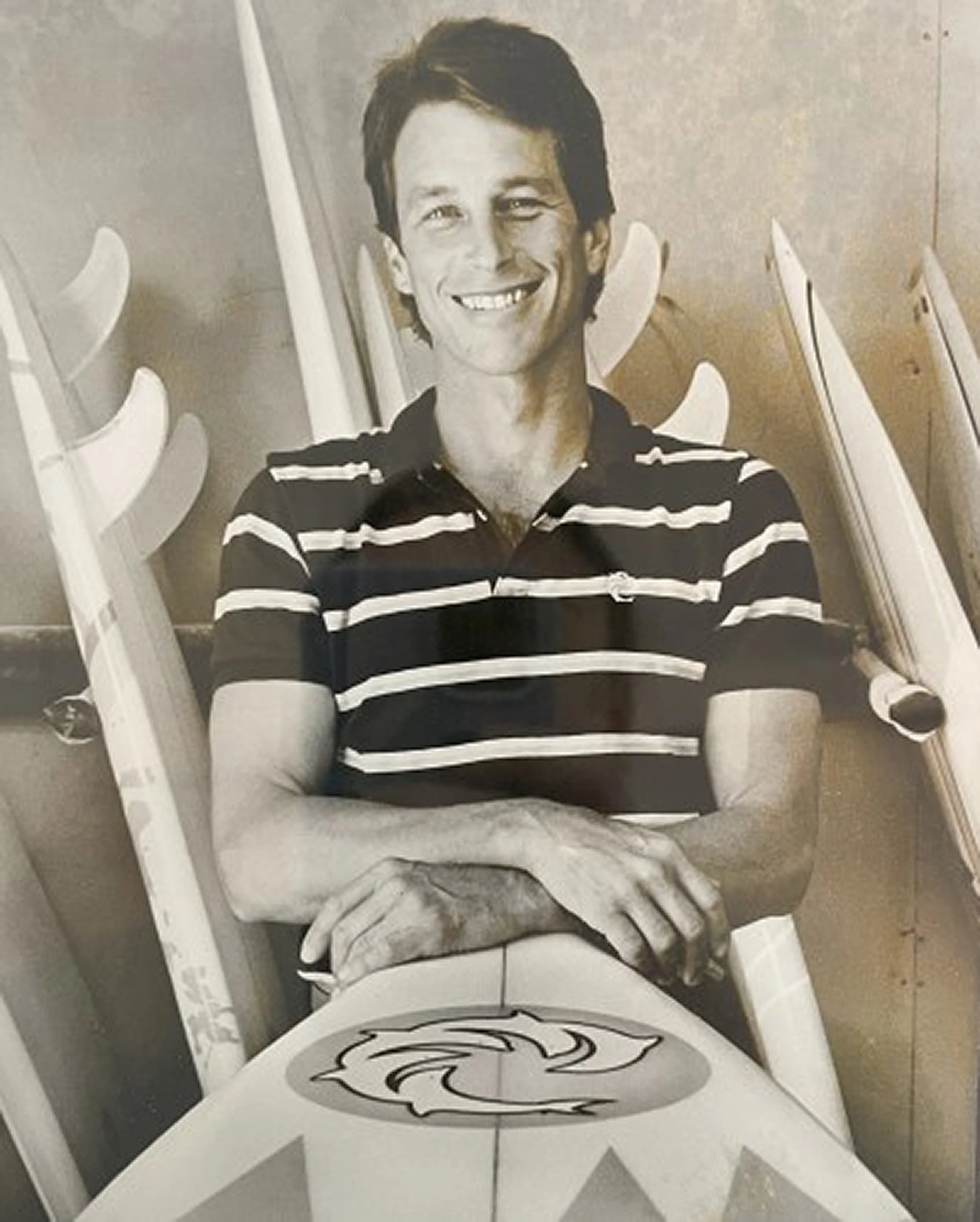

Surfers here assiduously pursue those small windows of time when the conditions are right, when light opposing winds compliment a maximum swell at optimum tide. And then they hope to avoid getting busted for missing work, skipping school, or backing out of plans made with a sweetheart. “There is something to be said for tenacity,” says Marty Keesecker, a Virginia Beach surfer and surfboard shaper of nearly 50 years. “If you put the time in, and you drive enough, you’ll find something to ride. If you’re patient and you don’t expect a lot, you’ll have fun and it’ll be enough to keep you in the water for an hour or so. In Virginia Beach, you can’t expect it come to you. You have to go to it.”

____________________________***____________________________

Not a great deal is known about the strange, imported, coffin-like parcel Walter F. Irvin brought back east from Hawaii in 1912. Irvin’s consignment, which would signal the coming phenomenon known as surfing, must have flummoxed terminal baggage handlers upon his disembarkation in Tidewater: a 9-foot long, 110-pound redwood olo. It was a gift for Irvin’s young nephew, James M. Jordan Jr. According to brothers Jimmy and Shep Jordan, Irvin’s grandsons, it was the first board of its kind on the East Coast.

In the following years, James Jordan would become locally famous for his exotic watercraft and wave riding abilities. For most eastern Victorians however, many of whom did not even swim, the spectacle must have all been taken with a novel, whimsical shrug.

Imagining the vast spaces of that era’s oceanfront—the place, the pace, the parcel itself. A young man shoulder-hoists the olo in a terse yet aloof jaunt from the waterline. Toweling off, squinting through the a.m. glare, he considers the tides and another paddle-out later. Victorian ladies stroll by the grassy beachfront lawns sheltered beneath parasols, palming their hats gaily in the summer breeze. Genteel glances and leisurely nods. The casual elegance of a time which moved to a different time. “Come Josephine in My Flying Machine” crackles warped and softly from a distant Victrola.

In the 1920s and 1930s, amidst the cedar shake grandeur of the Virginia Beach cottage-hotel era, each little redoubt had its own lifeguard. During that period, a few enterprising individuals would be the first to organize a formal beach service of lifeguarding and equipment rentals along the Virginia Beach oceanfront. Babe Braithwaite, John Smith, Hugh Kitchin, Dusty Hinant and Buddy Guy. The occupation known as “beach bum” was a long way off, but essentially they were pioneers of the surfing and beach subculture that would become a craze in subsequent decades.

And it wasn’t long before a new crop of lifeguard/surfers began heading to the oceanfront from Norfolk and various rural Princess Anne County communities. One of the earliest was Babe Braithwaite. An avid waterman and lifeguard, Babe hand built 4 Tom Blake model surfboards in Bobby Barcoe’s garage at Birdneck Nursery near where Oceana Air Base is today, and would often make the several mile trip to the oceanfront on horseback. Another was a Chesapeake Bay harbor pilot, Captain Robert Barrett Holland, who would head one of the most prodigious surfing families anywhere. His son, Bob Lee, has been a prominent member of the Virginia Beach surf scene for more than 70 years—from the 1930s to the present. All of his children also followed him into the water. Now in his 80s, Bob Lee is still surfing, most notably not on logs but on contemporary shortboards, a living bridge between eras and equipment.

____________________________***____________________________

Life During Wartime .- .- .- . -. -. -. 36.8506°N 75.9779°W

My late father, John Terrell Ferebee, Sr., a Norfolk native, was an avid Virginia Beach surfer from the mid 1940s through the 1980s. He hand-painted the French word coquette (flirt), on his board in a two-tone gothic script. He began surfing when he was 15, then became a lifeguard at the Cavalier Hotel and Beach Club on 43rd Street. The majestic old structure, the most iconic landmark of the entire oceanfront, was built in 1929 (the same year brewery tycoon Adolph Coors mysteriously plunged to his death from the 6th floor). Of course the hotel still stands today. One hopes it always will.

Legend has it that my father’s introduction into surfing occurred one blustery December morning during the august years of World War II. Following a Saturday night, which grew so late it became the next morning. A night which concerned pipes and tobacco, Lucky Strikes and Stan Freeberg records. Lively conversation soaked in Tidewater accents, more 19th century than 20th. And powerful, clear, amber liquid over ice in tall perspiring glasses.

At the daring invitation of fellow Norfolk native, the infamous Mason Gamage, they both paddled out into the stormy Atlantic. Nursing hangovers yet full of bravado, they manned two 13-foot wooden boards. In this modern world of high tech neoprene, it is almost impossible to even begin to comprehend this anecdote, a winter surf foray decades before the widespread use of the now vitally indispensable cold-water wetsuit. Nevertheless, a seed was planted.

The war years persisted as the graveyard of The Atlantic grew evermore packed with torpedoed merchant ships en route to Old Blighty. During what Winston Churchill referred to as 'the Merciless Peril’, explosions were heard frequently just off the coast here, and sometimes so close as to be seen. Sometimes a U-Boat of theirs, but more often than not, a ship of ours. Or of England's. The green gulf in those days was often braided with black Kriegsmarine oil, and on some occasions worse things were revealed at the high-tide-line. The war of the Atlantic was brutal. Even blackouts became mandatory in places. But as the lights went out all over Europe, summertime beach-life at Tidewater’s oceanfront would more or less still swing. The big band circuit still raged at the Cavalier Beach Club, Tea Dances daily at four, and Subway Parties at the Southend’s Sand Box. In the Blue of the Evening by Tommy Dorsey is this summers' dusk soundtrack; balmy-smooth jazz sophistication rules in the days before Rock and Roll.

In 1950, off in a cloud of JP-4, my father forsook his beloved beach boy lifestyle to fly F-86’s for the U.S. Airforce out of Kimpo in Korea. He returned five years later and began his career in the insurance business, resuming his surfing on weekends. He met my mother, Ann Meredith Stewart, in 1956 and they spent their first date sanding old varnish off his Tom Blake surfboard at a beach near the as-of-yet unnamed Rudee Inlet on the Oceanfront’s south end. It was an epic, though charming, first-date faux pas. She looks like Sophia Loren meets Laura Petrie. He looks like Gene Kelly meets Joe Strummer.

“At that time,” says veteran surfer Mike Clark, “there was no inlet and no pier at the south end. We could walk over to Croatan at low tide. Later, in the 1950s, I remember the building of the Steel Pier, fifteen blocks south of the Wooden Pier. You can tell a real native when they say Wooden Pier. That was how we referred to them—steel and wood.”

Norfolk native Scott McCaskey, a competitive surfer for more than four decades, also has fond recollections of the south end’s golden, post-war era: “Every day you were there, surfing at the Steel Pier, gave you the undeniable feeling you were in the right place at the right time.”

____________________________***____________________________

Pete Smith, age 71, is a mid-century grom. In recent months he has shared with me many anecdotes about the early days of surfing in Virginia Beach and the ways in which the scene has changed. Looking at photos from the 1960s, he can name every individual who surfed in that decade. In a shot taken in front of the erstwhile Mariner Hotel, Smith points out the different types of boards displayed by the diverse group of surfers in the picture: The first generation of hollow, wooden boards are held by the guys in the back row; the new fiberglass boards are held by the guys kneeling in the front row. In The Mariner Photo as Pete refers to it, there is Scott Taylor with an early balsa board, Bob Lee Holland and his youngest son Johnny, Bill Rap, Frank Butler, Butchy Kitchin to the right of his cousin Tommy Bryant. Dead center is Captain Holland. Then Waller Taylor, Pete Smith with his first foam Jacobs, Bob Gormley and fellow Cavalier lifeguard with Forbes Braithwaite, Richard Neal. On the top row holding the old wooden boards is Fred Johnson, Ricky Hall, Will and Don Pugh, Skip Rawls, Taylor Wainwright and lastly, Snooker Turner, who according to Pete Smith had the surfers' knees of all surfers' knees; visually whimsical and yet chronically painful golf ball contusions, the result of an alternate form of paddling a surfboard in the kneeling position. A recurring caricature motif of the mid-century longboard surfer.

Says Smith: “It was that transformative era where the old wooden boards were still around but the modern fiberglass boards were starting to show up. There was just so much community stoke and you knew everybody. There weren’t any crowds. You’d be looking for people to surf with, just to have someone to hoot and holler with.”

Significantly, a Californian named Les Arndt, then stationed at Fort Story, is also in the group picture. According to Forbes Braithwaite, Arndt was from Malibu and worked for top board maker Hap Jacobs before coming east for his military duty. “Arndt was driving past one day with another soldier,” says Braithwaite, “and saw me going surfing, carrying Scott Taylor’s balsawood board. He yelled, ‘Hey kid, where’d you get that surfboard?’” Arndt himself recollects that Forbes was about 12 at the time, and was walking across Atlantic Avenue at 49th Street. The chance meeting prompted Arndt to spend two years with Virginia Beach surfers, especially Bob Holland and his family.

Thanks to Arndt’s West Coast connections, the group started importing and selling what was, at that time, a rare and exotic specialty item—modern fiberglass surfboards from California. The group stored them in a garage owned by Forbes Braithwaite’s mother. In 1963, Pete Smith and Bob Holland opened the area’s first dedicated surf shop—Smith & Holland—one of the first businesses of its kind on the East Coast.

Not long afterward, Smith wrote a letter to Surfer trumpeting the burgeoning scene in Virginia Beach. He drafted the note on the letterhead of the Golf Ranch Motel on Laskin Road, which was situated on the southeast end of Birdneck Golf Course and owned by his uncle. He did not include a return address. John Severson, then editor of Surfer, showed the letter to Hobie Alter, who was the top California board maker at that time. Some months later, almost magically, Alter ‘just showed up' at the Golf Ranch Motel one day when Pete was working. Hobie was on an East Coast pushing his boards and had followed the breadcrumb-trail letterhead to its source in VB. He eventually negotiated a deal with Smith & Holland to carry his products exclusively.

As dedicated surf shops began to slowly appear in VB, and in a few cases, well before, surfboards were also being made available via utilitarian outlets: Western Auto carried Weber, Virginia Beach Hardware carried Hansen. Dawson Taylor at Fuel Feed stocked the initial Hobie’s in this area. And at Pembroke Mall across from where Skicoak used to be, Sears handled Bob White’s locally made pre-WRV boards, and The Sportsman’s Shop by the tuxedo place around back carried Dextra and several other California brands. And according to surfer/writer Scott McCaskey, even Martens & Davis Dive Shop on Colley Avenue in Norfolk supplied Yater, Con, and Surfboards Hawaii.

____________________________***____________________________

The early 1960s proved a pivotal time in modern surfing. In addition to the new availability of Hobie Alter’s boards on the East Coast, the first East Coast surf contest was started in 1962 at Gilgo Beach on Long Island. Bob Holland drove a group of Virginia Beach surfers to New York for the event, including Butch Maloney, Gary Rice, and an 11-year-old, whirlwind talent named Ronnie Mellott, a future Golden Gloves boxing champ in the Army, or so went the rumor in any event. And we all know how tale-telling goes amongst sailors, fishermen, surfers and pretty much anyone who’s ever loitered with intent down in Margaritaville. Either way, the guy was something of a badass. Bar, street, or lineup, you did not want to mess with Ronnie. Of the Holland clan, Mary Sydney Barker recalls meeting Ronnie Mellot: “I met him when I was in the 8th grade at Oceana High School. When the surf was good, he, Freddy Groskreutz, Bobby Chenman and a few others would leave school and go surfing. The principal always knew where they were and he would drive down to the pier and get them." Many of the VB guys took trophies at Gilgo that day, dominating the field completely.

In 1963, with cooperation from the local chamber of commerce, Holland, Maloney, and Pete Smith managed to move the pro-amateur surf contest to Virginia Beach, renaming it the Virginia Beach Surfing Festival. Two years later they changed the name again to the East Coast Surfing Championships, an event that has run for more than 50 years, drawing high-ranking surf talent from around the globe.

While perpetually upgrading its carnival bling to include many non-surf-stage-draws, such distractions threaten a diffusion of what is still implicitly touted as a surfing championship. Harking back to Chuck Dent’s prophetic rant-a-logue from MacGillivray Freeman’s classic 1972 surf film, Five Summer Stories, surf-culture and surfing itself often find themselves at curious odds. A hallowed tradition to some, a three-ring spectacle to others, the ECSC is the East Coast’s longest running surf competition.

Even from its very early years, the ECSC attracted world-class surfers such as David Nuuhiwa, Corky Carroll, and Mike Tabeling, along with the best locals. Near the old Cue South, Pete Smith would preside from atop a simple lifeguard stand at the Steel Pier site with nothing more than a clipboard, a visor, and a microphone, uttering witty, surf-speak-laced Southernisms in his consummate, slow-motion Tidewater accent. And yes, most people here still call it Tidewater, no matter what the Organizational Transformation Movement says.

____________________________***____________________________

By the middle of the 1960s, the West Coast-informed surf boom was fully realized here in the East. As the Cold War Era missiled into full swing, boards yet again were changing. This very place was changing too as, with scant official opposition, sketchy elements of gambling and racketeering persisted towards permanence at Tidewater’s Oceanfront. In those days, as Mayberry-By-The-Sea seemed hell-bent on becoming Vegas-By-The-Sea, Virginia Beach precariously edged toward resembling W. Somerset Maugham’s smirking description of the French Riviera: “A sunny place for shady people.”

In 1965, The Endless Summer opened at the madly mod, and very much missed, Buckminster-Fuller-design Virginia Beach Dome (a tragically demolished artifact of what would nowadays be considered a world-renowned tourism-draw of exemplary Mid-century modernism). Filmmaker Bruce Brown confirmed that he traveled with the movie in those early days of the films pre-voiceover release, and narrated live over a speaker system as the mellow twang of The Sandals soundtrack played from a reel-to-reel tape machine. He also ran a special preview of the film the night before, at a small party at Bob Holland’s house in Princess Anne Hills.

My mother and father were there at The Dome on opening night. My mother recalls Bob Holland’s youngest son, Johnny, zooming around barefoot on his skateboard, the newest must-have accouterment of 1960s surf culture. Johnny would become a standout competitive surfer, one of the most gifted wave riders this area ever produced, competing in the World Surfing Championships in California in 1966, going neck-to-neck along the way in preliminary events with many of this areas best surfers.

In June of 1968, Sports Illustrated did a cover story titled “Surfing’s East Coast Boom.” The cover photo, taken from the Steel Pier looking south, shows visiting legend Phil Edwards gracefully negotiating the micro-curl of a fair to middling right-hander breaking in the once sacred, now mythical, 75-yard zone between the north side of the First Street jetty and the south side of the pier. Only 10 years later, the rickety Steel Pier would catch fire and be demolished, obliging locals to rename the popular surfing spot as The Jetty or simply First Street, “a two-block surfing insane asylum,” according to Surfing magazine.

Edwards is quoted in the article, speaking to the core of the surf experience—beyond the contests, sponsorships, and commercialism: “I think maybe the best surfer in the world right now is some little kid whose name nobody knows. . . who is riding out there by himself, locked in some curl somewhere, having the ride of his young life.”

Local legend Allen White has fond memories of the Steel Pier era: "Summers for me in the late 60’s were amazing. I was the youngest guy on the Eastside Surf Team. I was only 12 and my mom had to get me a special permit to work for Al and Mouse (Sneblin) of Al’s Surfshop at The Steel Pier. I would work at the factory at night, repairing dings and rubbing rails. Then sleep behind the bait box and jump off the pier at daybreak to surf between the pylons and the jetty, which back then was just an insanely awesome break, and at times would break all the way through the pier and down the beach like a point break. What a experience for a kid that age! That's also when I met Ed "Cadillac” Townes. One morning, we were the only two guys out, and he gave me an awesome wave we were both paddling for. We were and are to this day, buddies for life over just that one genuine gesture. Thats how surfing is you know.”

____________________________***____________________________

Almost as quickly as the change in surfboards took place when the post-war 50s entered the Pop era, so too did longboards begin to obsolesce at the dawn of the speed-conscious mind shift which presaged the Shortboard Revolution. Spearheaded on a local level by pioneer shaper Bob White and his Wave Riding Vehicles quiver of space-aged foils, the new lines being drawn, hitherto unimagined, owed much to the radical vertical approach of freethinking American kneeboarder George Greenough, and creative template extrapolations based off his style of wave riding “involvement”, transposed to surfing’s upright mode, by innovative Australian surfboard shaper Bob McTavish. "Here come the warm jets."

VB’s first nationally recognized surfer of the new high performance generation was a lithe, flame-haired, scat-talking, wild-child named Jimbo Brothers. Something of a prodigy, a beach-blanket ragamuffin of Dickensian proportions, Brothers would dominate local and interstate competitions of the late 60s and early 70s—a sponsored team rider since the 7th grade, profiled in Surfer by the time he was 10. “One year the newspaper published a picture of me with my trophies and I was struggling to hold up the silver bowl and the wooden plaque at the same time,” says Brothers, now in his late 50s. “And the caption read, ‘Jimbo had more trouble with his loot than he did with the waves.’” So many other names stand out from this era as well: Joe Marchione, Chip McQuilken, the Smaltz brothers. “Chucky Charles was in a league of his own!” remembers Hawaii transplant Jeff Zirkle.

As the swinging 60s dwindled and the existentially ambiguous 70s reached cruising altitude, the contemporary shortboard milieu would dominate the kinetic surfing scene at both the Steel Pier and the Wooden Pier, as well as on early pioneering ventures to the sometimes world-class conditions of North Carolina’s Outer Banks. As Ronnie Mellott points out, “You can’t really talk about surfing in Virginia Beach without talking about OBX.” And my brother, Terry Ferebee echoes, “The lure of quality outer banks surf is what keeps alot of guys here still chasing the dream.” Even for Norfolk boys Gregg Bielmann and his brother Brian, a future world-class, Hawaii-based surf photographer, early-era Hatteras road trips were instigated fairly often in the hope of scoring uncrowded, proper surf. Where on many a nite-flite haul ‘down south' as the passing day changed guard with the new, as 11:59 made way for 12:00, as the previous night made way for the following morning, through the car speakers came Fire On High by ELO, in all its Baroque percussive grandeur, accompanied by that mellowly severe whisper of a voiceover: “K94 is WMYK-FM Elizabeth City / Virginia Beach. K94 is owned by Love Broadcasting and rocks the federally-assinged frequency of 93.7 megahertz with one hundred thousand watts of power from a thousand foot tower out in the woods near the edge of The Great Dismal Swamp. . . . K94 transmits 24 hours a day, 7 days a week. . . . . . WELCOME . . . TO THE BEGINNING OF A NEW DAY. . . . WITH K94.”

Anticipation. Adrenaline. Freedom. Presence.

But while the kaleidoscopic decade of changes pressed on, surfboards would go smaller and more spearishly radical. Viewed through philosopher Marshall McLuhan’s rearview mirror, decades stack up in idyllic compression, like so many Smithsonian dioramas, where diverse transformations occur in time lapse, all at once, both cultural and technological. And as another era exerts itself inexorably towards the future, and another checkered decade comes jangling to a close, another balmy Tidewater day wanes at the Oceanfront as Allen White smooths another wave to pieces.

____________________________***____________________________

Marc Theriault sends post cards from Panama.

Tail-ending the 60s and front-facing the 70s, a revolution in both surfboards and wetsuits will transpire, innovations which are, ironically, the by-products of the very military industrial complex so derided by the inner circles of the Vietnam-War-era’s surf-culture bohemia. During this timespan, a cast of characters straight out of Tom Wolfe’s “The Pump House Gang” rules the Steel Pier parking lot, that sacred zone consisting of stray dogs, ramshackle vehicles, surfer dropouts, and fishermen-widowers. Al’s Surfshop beneath the ramp of the pier smells of resin, bloodworms, incense, and wax. Nearby, foosball tables rattle and clatter with roll-fakes and crank-shots. “Trampled Under Foot” by Led Zeppelin blares from the Jensen triaxials of Jeff Duff’s forest green Karmann Ghia as it sputters along off Loop Road. Fifty-cent tacos at Speedy Gonzales on Great Neck & Mill Dam. Dusk sooths everything, and in the days before video killed the radio star, BYOB-surf-movie nights at the F.O.P. Hall round out the days of the seemingly never-ending, ever-present summer of the mid 1970s.

____________________________***____________________________

Digression:

Jumping off The Wooden Pier on big Northeasters. Outdoor showers at the Ramada at 7th St. where the boardwalk used to terminate before picking up again at 5th. Free cereal at The Traymore. Tuna melts and lime sodas from the counter fountain at Barr's Pharmacy. The acrobats on 21st St. near The Moon’s Hotel and The Ivanhoe. Biking around to check out the bikinied tourist girls through the deep end pool window at the Viking Motor Inn on 28th St.. Scarfing at the Belvedere after surfing Aeolus. Seaside Amusement Park on 30th & Atlantic where you could hear the fat lady laugh from blocks way in either direction, and in Doppler effect from a rusty Worksman pedaling by, to or from somewhere north or south. Quiktime Carwash. The Sunday Blue Law. Mike Flynn and his penny flattening machine. Summer before, it was his mobile Italian Ice carts. Summer before that it was puka shell necklaces sold up and down the beach. For all three, frequent handcuffs and court cases. Bearclaws at Carolee Donuts. Guitar strings from Danny Teagarden’s. The finger-carved inscriptions on G. Brocks' wax-covered Mercedes parked daily at Beach Pub.

____________________________***____________________________

The most notable stylist and competitor of the new guard was a 6'4" paddling machine named Wes Laine, who brought serious recognition to Virginia Beach and East Coast surfing in general. Laine placed ninth in the world on the pro circuit in both 1983 and 1985, competing in lineups as far flung as Hawaii and South Africa. “Wes was the first Virginia Beach guy to make it in the big time,” says Tim Sullivan, ex-VB surfer-shaper-turned-guitarist for the New-York-City-based surf music band, The Supertones. “He paved the way for other East Coasters.” Through Wes, vicariously, directly, or otherwise, The Free Ride generation found one of its exemplary representatives right here at our own beach-breaks. A local lineup was never more proud.

Owing to Laine’s pro-circuit success, there was a sharp rise in competitive intensity among surfers at the beach in the 1980s and 1990s, although both then and now most surfers simply continued to surf for the sake of surfing. By then it was not at all unusual for local surfers to explore Hawaiian-alternative, big-wave training grounds of Puerto Rico, following in the footsteps of early 1970s pioneers like Marc Theriault and Ronnie Mellott. Adding also to the area’s distinct identity is a continuing tradition of local surfboard making—niche-specific wave-tools, in theory anyway, better suited to the corporocity of Virginia’s swellular vernacular than many of the imported shapes built in California or Hawaii. The same tradition is alive and well today, noting talented young shapers such as Jordan Braizie and his Valaric label, and Austin Saunders at Austin. Throughout the golden era of the shortboard revolution and beyond, Bob White, Rosi, Con, America, WRV, Westwind, Bill Frierson, Bearcraft, Seasoned, and Hotline all bore the local standard. The surfer/shaper reigned in the days before automation.

____________________________***____________________________

When the 80s forced its way in on the preceding decade, some people stuck with the beach music program. With the pinks, the greens. And the Shag. Others moved on. Others still, never went there in the first place. Punk rock changed everything. So did the Thruster. The revolutionary three-finned board would hegemonistically dominate surfboard design for the next two and half decades.

The new modernity was exemplified locally by the enigmatic, freeform genius of Pete Smith’s son, Pete Jr., who was known colloquially in surfing circles as simply “young Pete Smith.” As Les Shaw, the owner of Wave Riding Vehicles, says, “You gotta understand. The most unsung, raw talent to ever come out of this area was young Pete Smith, with that stream-of-consciousness style he had. He was light years beyond everyone else in his approach.”

Of the Blaster era and the early Quad, there were other dynamic standouts as well. Later, the culminating decade of the millennium would introduce a whole new crop of competitive upstarts, such as Jason Borte, who would go on to dominate in contests, both locally and nationally. And most recently, local competitor Michael Dunphy has been making a name for himself.

“This is not my beautiful house; this is not my beautiful wife."

Here, as in other surf-cities, the age old quandary persists: surfing as pure sport and industry, vs surfing as pure art. Period. Surfing for surfing’s sake relative to the presence of other inextricably commerce-centered motives. The latter of which are unarguably fine in a cognizant world of perfect self-awareness. But flattening ones nose against verisimilitude, the chasm separating contrasting, at times closeted motives, becomes glaringly evident given a market-place which all too often, disturbingly, succeeds at conveniently subsuming the soul-surfing ethos for its own ends. Appropriation is appropriation. And thats the rendezvous of it. That a cannibal eats turnips doesn’t make him a vegetarian.

"Are there any soul-surfers still among us; still expressing the original vision?", asked freethinking 1960’s-70’s standout Chip McQuilkin, ruminating on the ever-encroaching influence of commercialism on surfing. “For without soul,” he warned, "there IS no vision.” Hidebound and quixotic to some, but the vulpine blandiloquence and crass evangelization which seeks to commodify the very soul of surfing, paradoxically and inevitably, will be the very thing which will send it all league upon league, fathom upon fathom down to Davey Jones’ Locker. As infamous California longboard legend Mickey Dora scrutinized all the way back in 1967, "I can’t help feeling there's something happening. New philosophies are taking hold...and I hope they want the same things I want: freedom to live and ride nature's waves without the oppressive hang-up of the mad, insane complex that runs the world …” With tongue albeit at least somewhat in-cheek, Dora’s reproof resembled something of a nod to President Eisenhower’s famous farewell speech, televised seven years prior in 1960, warning of the encroaching Military Industrial Complex. Dave Shotten at Freedom Surf Shop is eternally stoked, eternally optimistic, and yet similarly cautious: "We are the new kids on the block but at the same time we've been gifted a legacy and tradition that has been handed down from some of the pioneers who first put boards in the water in Virginia Beach. It's been a honor for me to hear the stories of the old days and to now have that message to pass down as I tell the story to another generation through visuals in the store as well as stories. Freedom Surf's vision is to look back into the past and celebrate what a surf shop really means. In this day and age the message has been lost. It's been diluted with Orange County propaganda that caters to a naive young audience that wants conformity.”

Today, interestingly, a freethinking new crew of stylists would seem to, at least potentially, defy Oscar Wilde’s maxim that youth is wasted on the young. Cam Fullmer, for example, grew up at the Northend and was taught by resident local Bud Easton. Now 21 and a sponsored longboarder, riding for Freedom Surf Shop locally and for Christenson in California, Fullmer and his tight circle are primarily the products of a neo-retro discipline, which would leave many diehard Thruster-era types in a state of bemused stupefaction. Rather than an aquatic reversion to the horse and buggy, their equipment is efficient and functional, especially given the consistently modest conditions. And there are other implications—both philosophical and cultural—that reach down into the very core of the user. “It’s less jock-like,” says Fullmer.

He often uses the word “motionlessness” to suggest what he’s after in his surfing, exemplify the super-soulful and stylish aesthetic of the new sincerity, ever-touting the merits of the old-school.

Contrary to some prior generations’ nonchalance toward their predecessors, Fullmer speaks reverently about local, old-school veterans like Bob Holland, Mike Clark, Mike Kalana, and Bobby Holland Jr. “Mike Clark is, what, like in his 70s?” says Fullmer. “And I mean, he can crank a turn. He can cross-step to the nose. He can ride in the pocket and work it with his knees and just ride a wave like its supposed to be ridden.”

Gesticulating with glancing, flat-hand motions, the way all real surfers do, he squints across at the radically changing psychic contour of the ever-developing oceanfront that he shares with his contemporaries. Theirs is a milieu that seeks retrieval from the past in order to move flowingly into the future, its creed ingrained by a reverence to history, tradition, and the old guys. In truth, most of the surfers here possess a core dedication to the art form. They also stay ever vigilant for those short moments of prime conditions, stitching them together over the decades, session by session.

Local landscaper Tommy Holland’s perspective sums it all up perfectly. He is a religious adept of the sunrise session. His attitude encapsulates the disentangled pure stoke of disentangled pure surfing. “For me it’s just about going. I have my mind set right now on the pier at 5 am tomorrow morning. Wind will be light NW for the first time this week. Might be good? Might suck. But I will be baptized before I deal with another day.”

Stay Free.

____________________________***____________________________

*

*An unintended eulogy: Several months after this article appeared in The Surfer’s Journal, Ronnie Mellott shuffled off this mortal coil towards some far-flung Big Tres in the sky. We all wish him well. Sun over the yardarm; in God’s name. †

_________________________________________________________

**One can never ‘thank’ people in a published magazine article. It simply does not happen. It happens in the prefaces of books. And it can happen online where ethereally, page space is not the commodity it is in print. Many people were interviewed for this article. But i would especially like to acknowledge the material contributions of the following: Scott McCaskey, Allen White, Tommy Kona, Mark Theriault, Rick Banta, Ed Townes, Tim Sullivan, Randy Laine, Marty Keesecker, Brian Bielmann, Jeff Zirkle, Mason Gamage, Terry Ferebee, Chris Ferebee, Jimmy Holmstrom, Amy Fisher, Reonda Cheng, Tyler Darden, and last but certainly not least, Pete Smith. . . . Thee Pete Smith. Thank You!

***Some of the imagery used here consists of archival material sent over the past several years from various people. If something has been used without permission, please email via the contact link. Additionally, if anyone has anything they wish to submit for inclusion, feel free to send (small files).

****Text herein revised from the original / Vah Beach, The Surfer's Journal 23.6 / Dec-Jan 2015 / ©Stewart Ferebee 2015